By Samuel Rubenfeld, Audrey Everist and Alexis Nicholson

January 19, 2022

A hacking group known in the private sector as MuddyWater was recently identified by the U.S. Cyber Command Cyber National Mission Force as a subordinate element of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS).

MuddyWater has primarily attacked Middle Eastern nations, but it also pursued European and North American countries, U.S. Cyber Command said Jan. 12, citing industry findings.

“These actors, known as MuddyWater in industry, are part of groups conducting Iranian intelligence activities, and have been seen using a variety of techniques to maintain access to victim networks,” U.S. Cyber Command said, providing technical examples for private-sector operators to spot in their own networks. “Should a network operator identify multiple of the tools on the same network, it may indicate the presence of Iranian malicious cyber actors.”

The hacking group had been active since at least 2017, according to CheckPoint Research. Late last year, threat intelligence researchers at Symantec attributed attacks on a string of telecom operators in the Middle East and Asia to MuddyWater, which is also known as Seedworm. Both firms had tied the hacking group to Iran, but not directly to the MOIS.

The U.S. government’s attribution marks its latest cyber-related salvo against the MOIS, an intelligence agency sanctioned a decade ago. Iran’s mission to the United Nations rejected the allegation in a statement to CNN.

The MOIS, which was established in 1983, is a leading agency coordinating Iranian intelligence activities. The U.S. sanctioned the MOIS in February 2012 for perpetrating human rights abuses against Iranians, as well as its role in supporting the Syrian government and Middle Eastern terrorist groups. In recent years, the main purview of the MOIS has been collecting intelligence on dissidents abroad using physical and virtual means.

The agency tracks activists through a network of agents posted at Iranian embassies, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service, but it also uses a range of cyber tools designed to gain clandestine access to targets’ potentially sensitive information. Israel’s Shin Bet intelligence agency recently revealed it had broken up an Iranian stratagem to recruit Israeli citizens as spies, according to media reports.

The U.S. has sanctioned multiple MOIS operatives over the years. Last fall, the U.S. designated four Iranian intelligence officials for acting on behalf of MOIS; they had been indicted for their alleged roles in a plot to kidnap a U.S. journalist and bring her back to Iran. Two senior MOIS officials were designated in late 2020 for their involvement in the kidnapping of former FBI special agent Robert A. Levinson, who the U.S. believes died in captivity.

And the U.S. has taken multiple cyber-related actions against the MOIS beyond the attribution of MuddyWater, according to a review by Kharon.

Surveillance of Iranians by MOIS Front Company Leads to Arrest, Intimidation

In September 2020, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Advanced Persistent Threat 39 (APT39), Rana Intelligence Computing Company and 45 individuals who worked at the firm in various capacities, including as managers, programmers and hacking experts.

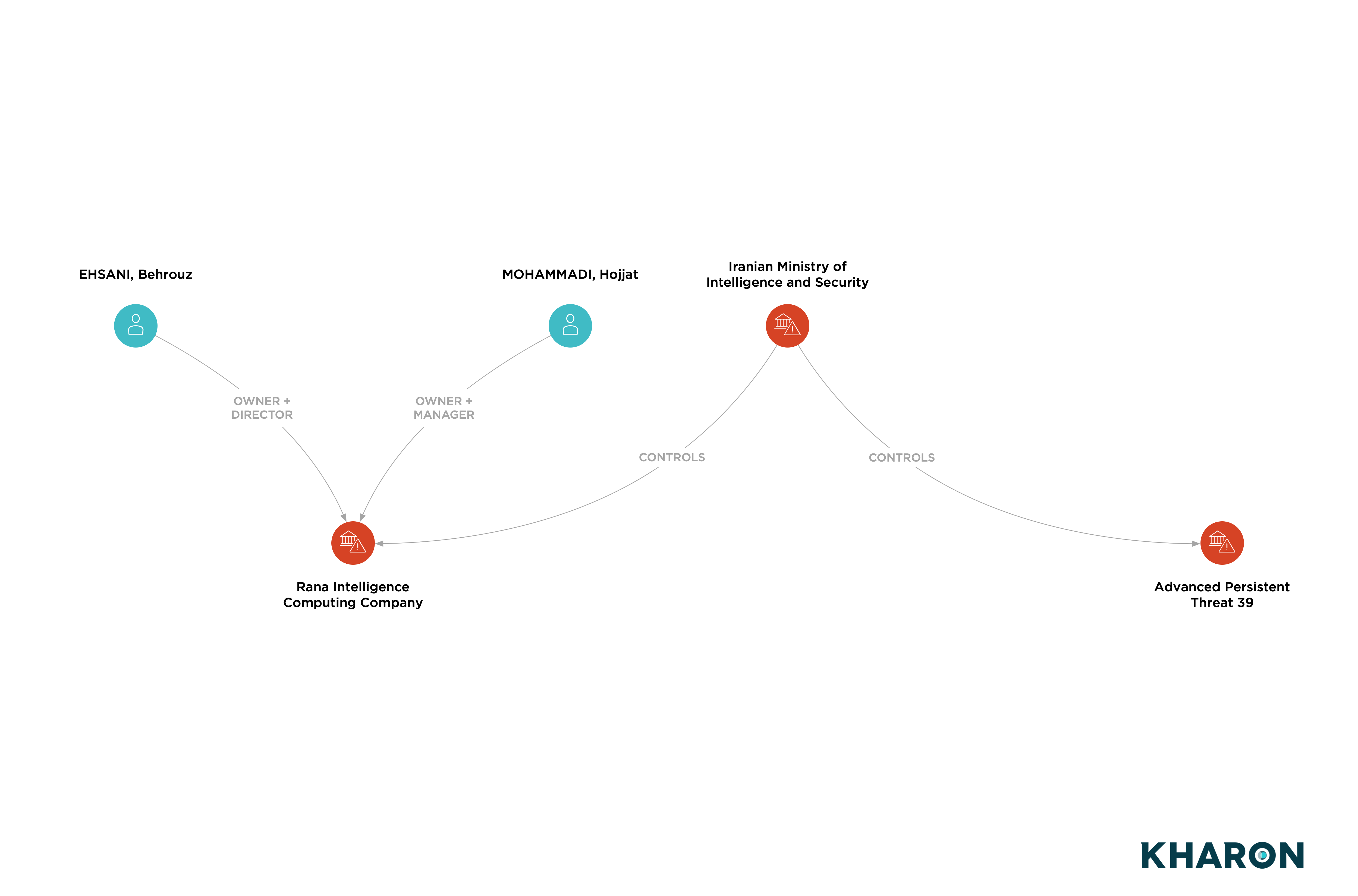

APT 39 and Rana were each designated for being owned or controlled by the MOIS, and the 45 people who worked for Rana provided support for MOIS cyber intrusions, the Treasury said.

Though controlled by MOIS, Rana is co-owned by two Iranian nationals, neither of whom were sanctioned by the Treasury, according to corporate records reviewed by Kharon.

The Iranian government used Rana to engage in a years-long malware campaign that targeted Iranian dissidents, journalists and international companies in the travel sector, according to the Treasury. The unauthorized access obtained by the individuals designated as part of the sanctions action allowed the MOIS to track individuals it deemed a threat, according to the Treasury. Some were subjected to arrest and physical and psychological intimidation by the intelligence agency, the Treasury said at the time. Rana’s targeting was both internal and global in scale, including hundreds of individuals and entities from more than 30 countries, as well as 15 U.S. companies, primarily in the travel sector, according to the Treasury.

APT 39 actors, meanwhile, victimized Iranian private sector companies and Iranian academic institutions, including domestic and international Farsi language and cultural centers, the Treasury said. Also among its targets were "air transportation and government” in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in 2018 and 2019, according to a whitepaper released in 2020 by the cybersecurity firm Bitdefender. APT39’s focus on travel and telecommunications suggested an intent to track specific individuals, cyber researchers at the firm Mandiant said in 2019.

Alongside the Treasury’s designation in September 2020, the FBI issued a cybersecurity advisory about APT 39, releasing details on eight sets of malware used to conduct its computer intrusion activity. The FBI also developed technical rules to help individuals and entities identify the malware on their own networks and systems, according to the advisory.

The sanctions and the advisory culminated a sweep of U.S. government action to disrupt and deter Iranian malicious cyber activity, the Justice Department said at the time.

Corporate Network Aids MOIS, Apparently Rebrands for U.S. Election Influence Effort

A year earlier, the Treasury had identified an apparent cyber campaign to access and implant malware on the computer systems of current and former U.S. counterintelligence agents.

Hossein Parvar, an affiliate of the Iran-based firm Net Peygard Samavat Company, had provided a group tied to MOIS with names, websites, email addresses and data associated with Americans, the Treasury said in 2019 when sanctioning him, the firm and several others.

Two Net Peygard managers were sanctioned at the time as well for providing technical support to organizations of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which is designated as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO), according to the Treasury.

Parvar was also indicted in the U.S. along with three other Iranians, including Net Peygard’s chief executive, for conducting computer intrusions on behalf of the IRGC. The charges were part of a plot that involved a former U.S. counterintelligence agent who had defected to Iran and assisted Iranian intelligence with targeting her ex-colleagues, prosecutors said at the time.

Net Peygard later rebranded to Emennet Pasargad, which was the company at the center of an Iranian effort to influence the 2020 U.S. presidential election, according to an indictment and sanctions designation late last year. However, the two firms have unique registration numbers and different directors and shareholders, according to corporate records reviewed by Kharon.