By Morgan Brown and Robert Kim

November 16, 2022

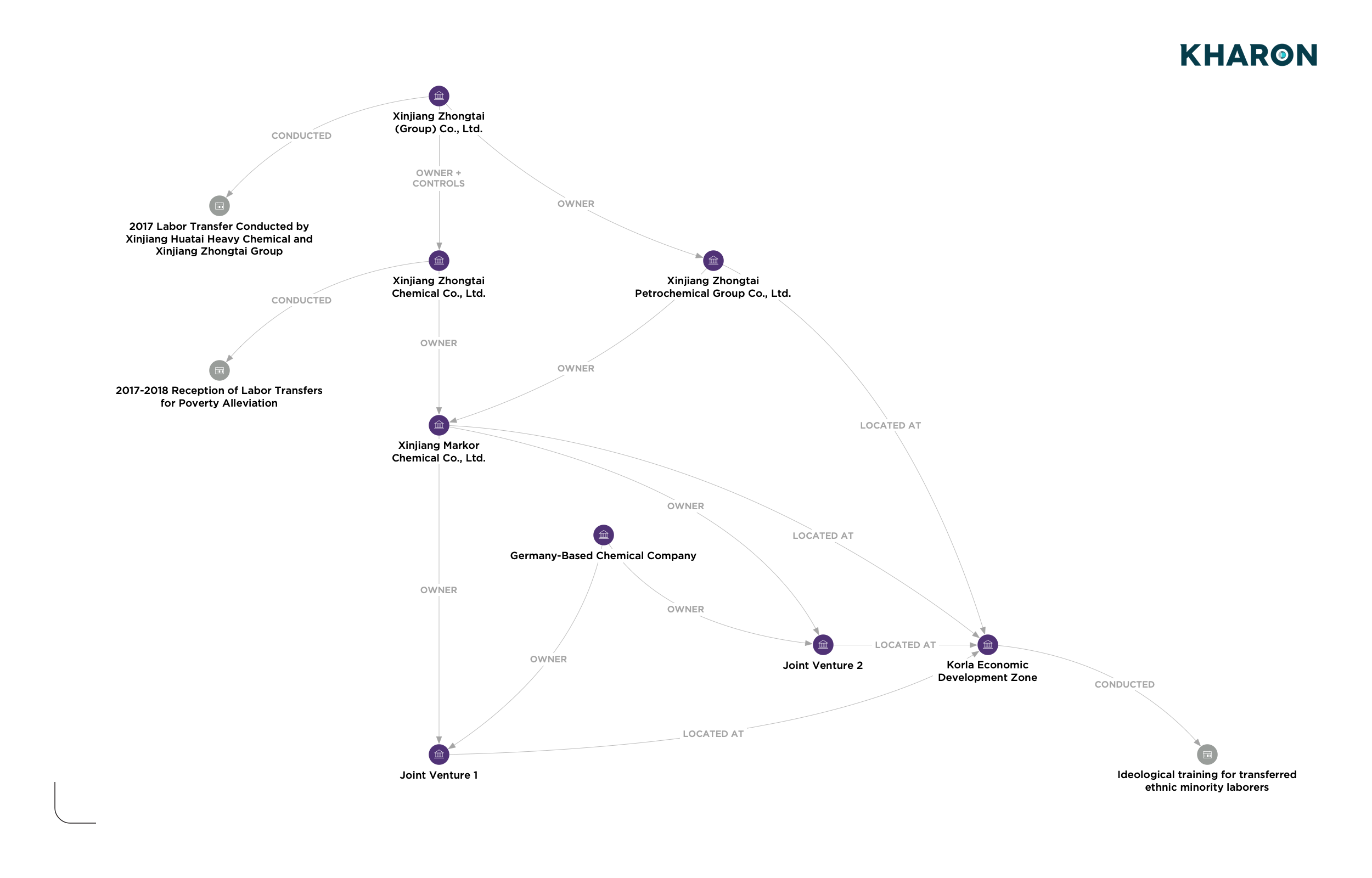

Two Xinjiang-based joint ventures involved in chemical production exhibit key indicators of the use of forced labor based on government advisories, a Kharon investigation has found. The two joint ventures are located in an economic development zone and owned by a state-owned entity that have both benefited from Chinese government labor transfers. The other owner is a European multinational company based in Germany and one of the world’s largest chemical producers.

Xinjiang Markor Chemical Co., Ltd., the local owner of the two joint ventures, is indirectly owned by Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group), Co., Ltd. — an entity owned by the government of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). The two joint ventures owned by Xinjiang Markor Chemical sell and manufacture several kinds of organic chemical compounds, such as formaldehyde, methanol, and butanediol, with many industrial applications, including plastics and textile production. The joint ventures are located in the Korla Economic Technology Development Zone, 250 kilometers south of Ürümqi, the regional capital.

Xinjiang Zhongtai Group and the Korla Economic Development Technology Zone have both received government-organized transfers of laborers in Xinjiang, participating in so-called poverty alleviation programs and providing patriotic or Mandarin-language education. The U.S. Government’s Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory has identified these practices as indicators of forced labor and other discriminatory practices targeting Muslim minority groups.

Between 2017 and 2019, Xinjiang Zhongtai Group received more than 3,000 laborers from southern Xinjiang transferred through poverty alleviation programs, according to a report by People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party-owned media group. Another report in state-owned media described workers transferred to Xinjiang Zhongtai Group undergoing “centralized education training” to learn “gratitude” toward the state.

The Korla Economic Development Technology Zone, where the two joint ventures are located, accepted more than a thousand laborers transferred from other areas of Xinjiang in 2017-2018, uses “ideological education” as part of its “poverty alleviation” efforts, and has set up national language night schools and cultural training to “change the thinking of transferred workers,” according to a 2018 press release. Labor transfers to the zone continued into 2020, according to the Xinjiang edition of People’s Daily.

No evidence was found indicating that either joint venture has used forced labor, but each was founded in 2014 and doing business in the Korla Economic Development Technology Zone while it was known to be participating in programs associated with forced labor.

Proposed EU Forced Labor Regulations

Imports into the U.S. of products made in Xinjiang have been generally prohibited under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) since June unless evidence is given that the goods were not made with forced labor, and a proposed EU regulation to ban goods made with forced labor from the EU market would create additional risks for importers of products made by joint ventures and other companies in Xinjiang.

The draft EU regulation proposed in September would ban from the EU market goods made with forced labor in any country. As drafted by the European Commission (EC), the rule does not refer specifically to China or the Xinjiang region, but preceding European Parliament resolutions indicate that forced labor in Xinjiang would be a leading concern under an adopted rule, especially when EU-based companies are involved.

A June resolution called for a ban specifically on products from Chinese companies exploiting forced labor, in addition to the global ban proposed by the EC.

In January 2023, the German Supply Chain Act (Lieferkettengesetz, or “LkSG”) will come into force, requiring companies with a corporate or branch presence in Germany to conduct due diligence into their supply chains for evidence of child or forced labor. A violation of the LkSG could result in a fine of up to 8 million euros depending on the nature and gravity of the violation.

___

For more information about the proposed EU regulations banning products made with forced labor, see Kharon's October 12 webinar The Proposed EU Ban on Forced Labor: Preparing for New Compliance Challenges.